|

TEXT SIZE: small | normal | large | huge |

|

U-BOAT OFFENSIVE17 |

|

| action was taken to divert all shipping from the Freetown Area, except those ships which must of necessity pass through those waters. Attacks on independents continued to increase as only about 20 per cent of the shipping sunk by U-boats in May was in convoy. In addition, the U-boats continued to move further westward and on May 20 located Convoy HX 126 at about 11° west longitude, before the antisubmarine escorts had joined. Eight ships were sunk before the convoy was forced to disperse. This attack forced iho adoption of complete transatlantic escort. It was felt that the considerable weakening in the number of escorts with a convoy must be accepted in order to provide some degree of protection throughout the voyage. Complete transatlantic escort was accomplished by basing escort forces in St. John's, Newfoundland, and escorting in stages from England, using Iceland as a refueling base. The Royal Canadian Navy cooperated in these measures by placing all available destroyers and corvettes at the service of the Newfoundland Escort Force. Canada had about 35 ships fitted for antisubmarine service at that time. The first escorts from St. John's sailed on May 31, 1941, and, as a natural sequence to this development, it was decided by the middle of June to escort the convoys all the way from Halifax. The long-endurance corvettes were to run all the way between Halifax and Iceland, with the destroyers being limited to St. John's. Areas of U-boat activity in June were further afield and wider spread than before, with reports of U-boats near Newfoundland and south of Greenland. Despite the magnitude of the elfort exerted, the shipping losses showed an improvement over May, with 57 ships of 296,000 gross tons being sunk by U-boats in June. Despite the increasing number of U-boats at sea, the losses were kept down by the efficiency of British countermeasurcs as five U-boats were sunk during June by surface craft. Losses in the Freetown Area were greatly reduced and the U-boats had difficulty in locating the transatlantic convoys. When they did finally locate Convoy HX 133 on June 23, the results must have been rather disappointing to the Germans, as only five ships were sunk at the cost of at least two U-boats sunk. This successful defense of this convoy was due in large measure to the fact that, when DF bearings indicated that HX 133 had been sighted by a U-boat, the escort was increased from one destroyer and three corvettes to two |

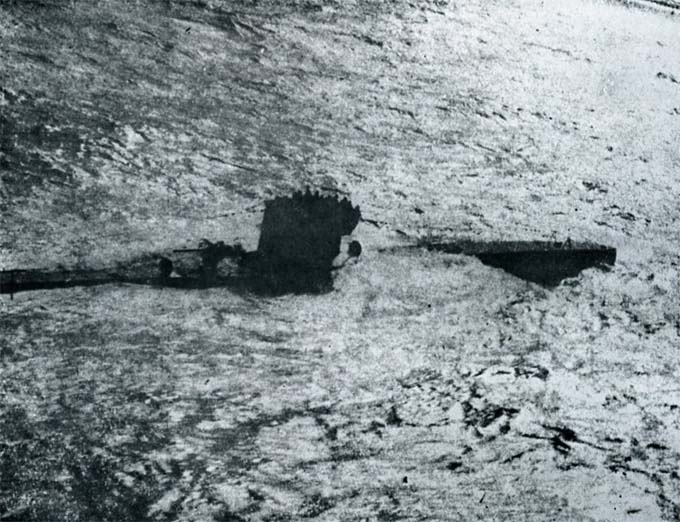

destroyers, one sloop, and ten corvettes. This was accomplished by taking the risk of stripping the escorts from two OB convoys within comparatively easy reach. Fortunately, one of these OB convoys escaped unscathed while the other suffered the loss of only one ship. On June 22, 1941, Germany invaded Russia and this seemed to end the threat of invasion of England for the time being. This released additional air and surface craft to help in the battle against the U-boats. In addition, German aircraft were diverted to the Eastern Front and attacks on shipping by aircraft were greatlv reduced during the last half of 1941. The average number of U-boats at sea continued to increase during July and August, but they had very little success as only about 23 ships of 90,000 gross tons were sunk in each of these months. This meant that the average U-boat at sea in the Atlantic was sinking less than one ship a month, a much lower rate than had been experienced in the past. In an endeavor to make the interception of shipping easier the U-boats withdrew to the eastward towards the end of July and concentrated in the waters west of Ireland and to the east of 25° west longitude. This placed them at a focal point of shipping where they could intercept both the East-West and the North-South convoys. However, the U-boats had no better luck there in August than they had in July. By this time, even the Gibraltar and Freetown convoys had more or less complete end-to-end escort. Towards the end of August, there were indications that the U-boats were resorting to long-range attacks on convoys, probably firing a browning salvo, and also to deliberate attacks on escorts. This policy of attacking escorts might have proved more profitable in the earlier days of the war, when the number of escorts with convoys was much smaller and when the general escort situation was much tighter. In addition to the defensive successes scored in August, this month was marked by one of the outstanding events of the U-boat war, the surrender of U-570 to a Hudson aircraft on August 27, 1941. U-570 left on her first cruise on August 24 and was at sea for only 74 hours before she surrendered. The U-boat came to the surface at 1030 on the 27th, the precise moment the Hudson from Squadron 269 was overhead. The U-boat tried to crash dive but the Hudson was too quick for her, diving from 500 feet to 100 feet, and dropping four depih charges. Captain Rahmlow, believing the U-boat more seriously damaged |

| CONFIDENTIAL | |

|

18START OF WOLF PACKS; END-TO-END ESCORT OF CONVOYS |

|

Figure 1. Surrender of U-570 (HMS Graph) to Hudson aircraft S-269 on August 27, 1941. Note German crew crowded into conning tower. |

|

| than was actually the case, ordered the crew to put on life jackets and go to the conning tower. The Hudson opened fire and kept the crew from abandoning the U-boat. After a white flag was displayed by the U-boat the Hudson guarded it until relieved by a Catalinn. A trawler arrived at 2250 and U-570 was towed to Iceland. She was subsequently repaired and re-christened HMS Graph, proving an invaluable addition to the British Navy. This was the first U-boat actually captured by the British and proved to be an extremely valuable source of information about the operating characteristics of U-boats. U-boat activity continued at a high level in September and their intensive efforts met with greater success than during the previous two months. Allied shipping losses rose sharply to 51 ships of 205,000 gross tons sunk by U-boats, with 70 per cent of the tonnage sunk being in convoy. This increase was due in a large measure to the severe casualties suffered by |

four large convoys as a result of determined and sustained attacks by wolf packs. Two of these convoys were slow SC convoys which were intercepted and heavily attacked south of Greenland, losing 21 ships and one escort. Two U-boats were sunk by escorts during these attacks. The other two convoys, homeward bound from Freetown and Gibraltar, lost 15 ships and one escort to the U-boats. However, in viewing the situation at this time it would be well to compare it with the previous year. In September 1940, when about seven U-boats were at sea, the losses to U-boats were about 300,000 gross tons. In September 1941, when there were about 35 U-boats at sea, the losses to U-boats were only about 200,000 gross tons. In September 1940 the U-boats were attacking convoys with impunity. Rarely was a U-boat sighted during her attack, and even more rarely was she counterattacked. In contrast to this, in September 1941 it was a matter of the keenest |

| CONFIDENTIAL | |

|

U-BOAT OFFENSIVE19 |

|

| disappointment it a convoy were attacked and the enemy escaped unpunished. The limited

number of escorts, usually about one destroyer and three or four corvettes, although unable to prevent the U-boats from

attacking the convoy, were generally able, with the help of covering aircraft, to shake off the pursuing U-boats by persistent counterattacks. No convoy was attacked for more than three successive nights in September 1941. The effect of Coastal Command aircraft on U-boat operations may be seen by the fact that, of the tonnage sunk in the North Atlantic during September by U-boats, about 75 per cent was lost in the area outside the economical range of Whitley and Wellington aircraft (100 miles). Aircraft made 45 sightings and 39 attacks on U-boats in September, the highest monthly figures recorded to that date. September was also marked by the introduction of HMS Audacity, an auxiliary aircraft carrier, as a convoy escort. One of her fighter aircraft shot down a Focke-Wulf attacking the rescue ship of Convoy OG74. As the radius of U-boat operations in the Atlantic extended further west and U. S. ships were being sunk by U-boats, the U. S. Navy announced on September 15, 1941, that it would provide protection for ships of every flag carrying land-aid supplies between the American continent and the waters adjacent to Iceland, on which a U. S. base had been established in July 1941. On September 16 the first convoy (HX 150) to have U. S. Navy ships as part of its escort sailed from Halifax. The losses in October 1941 dropped to 32 ships of 157,000 gross tons sunk by U-boats. Only one convoy (SC 48) was heavily attacked by U-boats; nine ships and two escorts were sunk and the USS Kearny was torpedoed but arrived at Iceland. The USS Reuben James was sunk by a U-boat torpedo on October 31 while acting as an escort of Convoy HX 156. In a number of other cases the convoys were located by U-boats but the escorts were able to drive them off without suffering serious losses. An interesting feature of the operations during October was the disinclination of the U-boats to pursue their quarry too far northward or eastward, presumably because they did not care to enter the areas swept by Coastal Command aircraft. This is indicated by the fact that of the 26 ships sunk within 800 miles from air bases, 14 were lost in portions more than 600 miles out and 12 in the 400 to 600-mile |

zone (covered lightly by Catalinas). No ships were sunk within 100 miles from Coastal Command bases. This meant that the U-boats were being forced ever further westward, with consequent greater wastage of time and U-boats, particularly in winter. In addition, air attacks on transit U-boats in the Bay of Biscay began to increase in frequency and effectiveness, thereby further cutting down the operational time of U-boats. During the first week of November, the scale of the U-boat effort was probably the greatest and the scope of their patrol the widest spread of the whole Atlantic campaign up to that time. When Convoy SC 52 was intercepted shortly after rounding Newfoundland and four ships were sunk on November 3, it was considered prudent not to risk it upon a transocean journey for the greater part of which many U-boats might have maintained continuous harrying attacks. The convoy put back to port and the ships sailed later in Convoy SC 51, which consisted of 71 ships. This decision proved fortunate, as there followed a period of successful evasion which lasted for the remainder of the month. The total losses for November 1941 dropped to 12 ships of 62,000 gross tons, the lowest figure since May 1940. Weather contributed to the reduction in shipping losses but the main factor was skillful evasive routing. Successful evasion meant fewer chances of contacts between escorts and U-boats and therefore less chance for the destruction of U-boats. In the meantime the British offensive in Libya had been launched and the Germans withdrew a large proportion of their U-boats from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean to help the Italian Fleet and temporarily, at least, to use their U-boats for the transport of military supplies to Rommel. Toward the end of November, convoys from Gibraltar were suspended and every available ship was used in an endeavor to close the Straits of Gibraltar to the passage of U-boats and to destroy U-boats attempting passage. Two German U-boats attempting the passage were sunk during the month, one by surface craft and the other by a Dutch submarine. The perceptible slackening in tension in the North Atlantic that started toward the end of November continued throughout December 1941. The losses in the Atlantic continued at a very low level, with only 10 ships of about 50,000 gross tons sunk by U-boats during the month. Howvever, the tendency of the U-boat war to become world wide became apparent, |

| CONFIDENTIAL | |

|

24START OF WOLF PACKS; END-TO-END OF CONVOYS |

|

| U-boats at sea, while shipping construction was gradually increasing. However, from an offensive point of view, the U-boats were still relatively safe. Surface craft acting as convoy escorts were the only serious threat to the U-boat, although aircraft were gradually becoming more effective in harassing and damaging<

|

U boats. It seems, therefore, that the general situation in the Battle of the Atlantic at the end of 1941 was roughly the same as the situation which prevailed at the end of World War I — that is, with shipping losses checked, but with the U-boats relatively safe at sea. |

| CONFIDENTIAL | |

- On to ASW in World War Two Part 1: Chapter 4 -

ASW in WWII Home | Researcher@Large Home