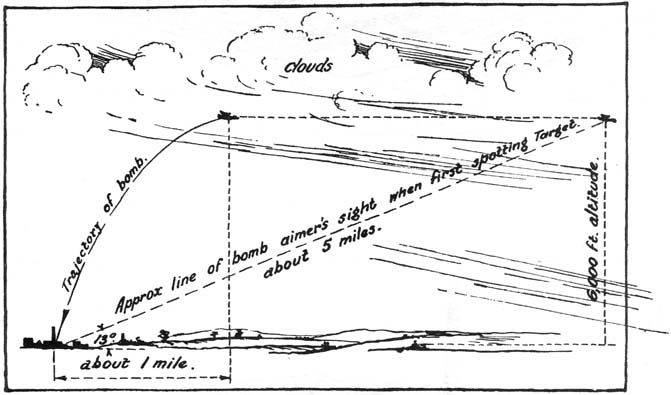

| Figure 1. | Bomb Aiming. This illustration shows the distance from which a target must first be located if accurate bombing results are to be obtained. (Typical dimensions). |

If you can see this text here you should update to a newer web browser

Normal | Highlight & Comment Highlighted Text will be in Yellow.

|

CAMOUFLAGE FOR NAVAL SHORE ACTIVITIES

NAVY PASSIVE DEFENSE HANDBOOK NO. 1

Prepared by the Bureau of Yards and Docks

March, 1941

|

|

Table of Contents

i |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ii |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

- 1 - 1. Caution: Much has been written on camouflage experience in the last war which would not be applicable in these times on account of later developments. 2. Camouflage Objectives at Naval Stations: Nearly all naval shore activities, being contiguous to well defined shore lines and in some instances covering many acres, are easily located by experienced aerial navigators, and the proportions of some of the structures make them easily distinguishable at long distance. Under such circumstances hiding a large establishment from aerial observation is in most cases impossible. Provision should nevertheless be made to confuse low-angle visibility observation--that is, against visibility from the "bomb-aimer's angle." 3. Long distance planes with a heavy load of bombs normally drop their bombs while flying on a more or less horizontal course. It is to them that the "bomb-aimer's angle" applies. Dive bombers are more difficult to camouflage against, but they at present are more in the nature of light, fast, short-range craft. Attacks on most U.S. Navy activities at present are likely to be by planes flying a near horizontal course. It is true that photographic reconnaisance (SIC)is likely to consist largely of vertical shots, and camouflage from all viewpoints is therefore in order; but it should be particularly effective from the low angle at which a heavy bomber would need to recognize it in order to make a hit 4. Importance of the Concept: An understanding of the concept of "bomb-aimer's angle" is vital to the proper planning of camouflage. To illustrate, assume that a particular station is selected by an enemy for attack, and that it is decided to bomb some vulnerable point that will have a most crippling effect. If the station has local ground defences in the form of balloon barrage or anti-aircraft guns, or both, an approaching bomber will be compelled to fly at a considerable height. In order for the bomb to reach the selected objective, it must be released at a considerable distance in advance of the target, the particular distance in any case depending on the height and speed of the plane and the weight of the bomb (Fig. 1). To achieve any degree of accuracy, the bomb sighter must have a fairly continuous and clear vision of the target for a considerable distance in advance of this "deadline" . 5. How Camouflage Complicates the Bomber's Work: From this

|

|

- 3 - 8. By "form" is meant the outward or visible shape of a solid body as distinguished from its texture or its color. 9. The various surfaces which comprise the outer faces of a solid object, when subjected to a source of strong light, reflect different values of tone, according to the direction of the light source and the position from which the object is viewed, and it is from these various outlines that the form is recognized. The contrast of light and shade becomes more pronounced when viewed from certain angles, on account of the shadow cast by the object on the background, and the outline is accentuated by the depth of the adjoining shadow. 10. Under certain conditions the form of an object, although clearly visible, may be difficult to define accurately, for the reason that the surface tones are very uniform; but should the object be observed under a direct source of light, it may be identified by its shadow. For example, an upright pole when looked at from a verticle position would appear as a circle; but should there be a shadow, the combination of circle and shadow would identify the object as a pole. 11. A building with a peaked roof is more easily defined than one having a flat roof, on account of the difference in value of reflected light from the two surfaces of the peaked roof as compared to the single tone reflected by the flat roof; and similarly, a building with a saw tooth roof is still more liable to be recognized, by reason of the regularity of the alternate roof surfaces, These variations in tone are caused by the amount of reflected light from each surface of the roof, and depend upon the position of the source of light (Fig. 2). Vertical wall surfaces will register totally different values, according to their relative positions, and by analyzing these various tone values, the shape or form of the object is determined. 12. An observer may distinguish between man-made objects and those that are natural, by noting differences in color and tone, and in light and shade, as compared to the natural background. These variations are usually recognized in the long, straight lines of walls and roof, and the different tones of the outer surfaces. It is the purpose of camouflage to eliminate those incriminating features. 13. It should be remembered that structural camouflage, in the form of either nets or excrescences, should in itself have

|

|

- 4 - an unidentifiable form if the object is to be successfully protected. 14. "Matt" and "Glossy" Textures: All surfaces exposed to light have "texture", whether they be surfaces covered with vegetation, vacant land areas, the exteriors of buildings or structures, or bodies of water. Texture, or quality of surface, may be generally classified as either "matt" or "glossy".15. The amount of light reflected by any surface depends upon the texture of the surface and upon the angle the surface makes with the sun's rays. The smoother a surface is, the greater the amount of specular reflection. Smooth reflecting surfaces will appear dark, however, if the light is not reflected to the eyes of an observer or camera; on the other hand, the majority of natural surfaces appear intermediate in tone through a wide range of lighting conditions because they dissipate some light in all directions. 16. Rough and irregular "solid" surfaces may be considered as consisting of a number of reflecting facets of various sizes, inclined at different angles. The nature of the object will determine the quality and size of the facets and the possibility of their reflecting light 17. Painted surfaces must be considered from the standpoint of texture (Fig 3), because at certain angles the reflection of the sun on a painted surface may be such as to blind out all color that may be applied. For this reason, even ordinary flat paint is best not used in camouflage, as the surface still lacks the necessary matt texture to dissipate or overcome reflection, unless it is roughened by introducing materials that will absorb and scatter the reflections (See Paragraph 80). 18. Texture of Various Natural and Artificial Surfaces: The following paragraphs describe, in a general way, the appearance of a few natural and artificial features that may be anticipated in ordinary landscape photographs, and will be a guide in selecting colors that are to match adjacent natural terrain; Trees, bushes, scrub and hedges, on account of the mixture of reflection and shadow, appear in shades from light green to black under summer conditions. Thus, woods appear patchy, because some trees reflect more light than others and tend to counteract the effect of color and shadow. Isolated trees and bushes appear as a circular dark green spot at the end of a slightly darker shadow. Orchards are distinguished by the regularity

|

|

- 5 - in spacing of the trees. Scrub, usually mixed with, grass or sand, appears as darker patches on a lighter tone. If the scrub is thick, shadows will be visible. Hedges appear as dark, irregular lines, with or without shadows, according to their height and the angle they make with the sun's rays. Grass, marshland and swamp. Viewed from above, grass presents a broken surface, reflecting little light. Its appearance depends partly on its length and the consequent shadow, and partly on the wind, which alters the angle of reflection. Short grass appears lighter, as it presents a better reflecting surface and may show the soil underneath. In general, grass is between light and medium green. Patches of coarse grass, as in a marshland, are dark green with a mottled appearance, and where they merge into wet areas are still darker, with patches of black and the same mottled appearance. Crops. With crops, the same conditions apply as with grass. The young crops are light in tone, on account of the reflection from the ground. As they grow, the tone darkens, with lighter patches appearing where the growth is beaten with wind and rain. Ripe, upstanding crops usually appear light in tone, while large-leafed crops, such as beans, tobacco, etc. often present a mottled green appearance, due to the contract between reflecting leaves and shadows. Tilled and dressed soil appears as a light brown earth color, depending on the soil type, and fresh ploughed ground varies from white to dark brown, depending on the angle of vision and the source of light, but is usually quite distinct from neighboring unploughed land. Sand, providing it has a comparatively smooth surface, appears almost white, and deeper tones may indicate slopes. Rock varies from white to black, according to surface and the depth of shadow. Water, except where it reflects light from the direct rays of the sun, appears dark gray or black or may in some localities assume a variety of other colors. If the water is shallow, with a light or weedy bottom, it reflects more light and appears as a lighter gray. Rough water presents many reflecting surfaces, and white patches appear in areas that are more disturbed. If

|

|

- 6 - water is ruffled by a breeze, these patches tend to have a definite form characterized by straight lines. 19. Any colored surface possesses qualities both of "color" and of "tone". "Color" is well understood (red, blue, green, and so forth). "Tone" is judged by the amount of light reflected by the color; in other words, it is the shade of the color. 20. There is no general method of measuring the various tones that a color may possess, and one tone cannot be said to be so many tones lighter or darker than another tone of the same color. However, for the purpose of blending-in an object that is being camouflaged with the normal background, standardized tones of colors are used to facilitate the work in the field (See color charts at end of this handbook). In connection with such work it should be remembered that color applied to a small area appears to have a different shade, or tone, from a large area covered by the same color. 21. Tone, or shade, is due almost entirely to the amount of light reflected by the object, and reflection in turn depends on a number of factors, such as the position of the sun and the texture of the surface. Color may sometimes affect the tone slightly, but its effect is relatively so small that it may be neglected. 22. To understand the general appearance of ground features as they appear on photographs, two factors affecting the photographic tone, or depth, must be appreciated. These are the photographic tone value of color and the reflection of light. Thus, a tarred macadam road, owing to its color, should appear black, but on account of its texture and the indirect light which is reflected, it appears to be dark gray. Where the sun is reflected directly from its surface, the area appears definitely white, shading off to gray again on each side of the reflecting point. Concrete roads, owing to their color, appear to be almost white, and the surface, though rough, is flat, and therefore reflects indirect light to some extent, adding to the white appearance. But the rough surface texture does not reflect the direct rays of the sun to the same extent as the smoother surfaced tar macadam road, and, therefore, does not appear to be quite so white as the brighter parts of the latter. 23. Difficulties of War-Time Observation: An aviator on a reconnaissance or bombing mission over enemy territory is faced with a variety of difficulties. In the first place, he may have no advance knowledge of meteorological conditions existing in the

|

|

- 7 - region; second, the territory over which he is flying may be unfamiliar; and finally, he may have to contend with attacking planes or anti-aircraft guns. All these factors distract his attention. 24. Landmarks: Before leaving his base, he may have familiarized himself with ground conditions, to some extent, by consulting maps and aerial photographs of the region in which his target is situated; and to definitely locate the object of his mission he is usually guided by established landmarks which may be clearly visible at long distances. These landmarks will often be shore lines, rivers, railroads, highways, and canals, all of which are easily distinguishable and appear as long continuous ribbons in the landscape. With study, features in each may be selected that can be correlated in such a way as to direct him to his objective. These features of background are difficult and in most instances impossible to eradicate, unless by the use of smoke, which obliterates all vision of the terrain below (see Section VI-F (This is a separate Booklet I have not scanned in yet)). 25. Other tell-tale indicators are to be found in and around naval shore establishments and general industrial areas„ Among these are tall smokestacks, hammer head cranes and gantrys, radio towers, tall buildings, large acreages of factory roofs, and the clear expanses of landing fields with their well defined runways and warming-up aprons. All these objects definitely locate activities of which they are a part. However, though difficult to camouflage, they can be treated in a way that will minimize their conspicuous appearance. 26. Importance of Matching Background: To satisfactorily accomplish a defense by camouflage, the background is of the utmost importance. By studying the general landscape an aviator is able to locate the area in which his target lies, from the various landmarks previously selected. But if the camouflage has been well done, and matches the background, the aviator will still have difficulty in positively identifying his objective, be it a small isolated structure or a large establishment (Fig. 4). If this happens, camouflage, will have achieved its purpose. 27. Instances have been observed where a costly application of dazzle paint camouflage adorned a large building, surrounded by groups of other buildings to which no consideration had been given; and other instances where a very small and intricate pattern of dazzle paint, usually of soft pastel shades, had been applied on buildings similarly situated. These practices are sheer folly, not only from the consideration of cost, but from the standpoint that no thought had been given to the background. 28. An observer would not require much experience to be

|

|

- 8 - attracted to objects of this nature, as anything that appears out of harmony with the surroundings invites immediate attention. The first mentioned would arouse suspicion by appearing conspicuously alone, and in the second instance the small-pattern pastel design would appear "flat" and would not alter the appearance of the structure. 29. Whether a building or structure be located in open rural countryside, in an urban district, or in an industrial area, the background must be well studied by taking note of the normal features in the area-—the types of homes, color of roofs, and other pertinent items. The camoufleur's aim should then be to carry out a scheme that will duplicate the general background as far as possible in colors and tones, at the same time breaking up outlines (both structural surfaces and shadows) in such a way as to make the object appear "natural" in the area (Fig. 5). 30. General Methods of Matching Background: Satisfactory results may often be obtained by the use of paint or nets; or by some form of structural camouflage, such as the addition of excrescences on the upper surfaces; by appendages that may be attached by outrigging on the sides, or by any other means that may be practical, depending on the circumstances. It must be borne in mind that no specific standards exist nor can instructions be offered at this time as to what should be applied in each instance. Each is a problem in itself, depending on its environment and nature, and must be handled as such, however, suggestions are offered later in this handbook that may apply in certain cases, and which will be helpful in a general way in guiding those entrusted with the work in each activity. 31. The Concept of Disruption: As previously stated, an observer's attention in seeking a target is immediately directed to any ground feature that appears unnatural in the landscape. It is the purpose of camouflage to endeavor to "disrupt" those features to an extent that will make them appear less conspicuous, by blending the object with the adjacent areas. In nature, this principle is the only protective defense which certain animals and birds possess against those seeking to destroy them. 32. Disruption as Applied in the Last War: During the last war, it was advocated by some authorities that camouflage should be distinctive to the point of being outstanding, and this principle was based on "hiding" objects or activities by making them appear to be something conspicuous but indefinite. This principle of disruptive camouflage was extensively used in the camouflage of ships. It is admitted that the method made a vessel indefinite as to features and difficult to recognize, and the effect caused

|

|

- 9 - confusion as to the actual direction of travel, but it defeated the purpose of camouflage by making the vessel much more conspicuous and an easier target to see. 33. Disruptive Patterns: Any pattern inserted in a background should blend into the background so that the general outlines of the object are not discernible (Fig. 4). It is not sufficient, in carrying out a scheme of camouflage on an object, to limit the work to the object itself. This would have very little disruptive effect, although it would disrupt the general features of the object. The pattern should rather be designed to extend over all roof edges and be carried out beyond the wall lines to the adjacent ground areas, which should meet the natural background and blend into it. making the whole appear as "natural" as possible (Fig. 6). In treating a number of similarly constructed buildings within an area, it is particularly important to avoid repetition of pattern,, An object, when viewed from a distance of 5 miles, must be about 6 feet in its least dimension to be seen, and it is recommended that this rule be observed In the planning of any design. 34. Selection of Colors: In selecting the colors to be used, a certain degree of boldness is recommended, in order to allow for fading; but reason should be exercised, as otherwise the result may be to the extreme and appear conspicuous--the precise opposite of the original intention. The more naturally the color and textures blend with the surrounding areas, the more effective will be the result.

|

|

- 15 - IV. DETAILS OF AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHY 47. As pointed out in Section III-B, consideration must be given to the possibility of enemy reconnoiteriiig planes approaching a target and securing photographs which may reveal very valuable and definite information on the extent of activities and on new work that may be under construction. A knowledge of the principles of air photography is therefore important to the camoufleur, both in planning his layouts and in testing his results. 43. Types of Photographs: Air photographs are taken with the camera depressed below the horizon (obliques), or pointing straight down (verticals). Neither type of photograph appears quite natural compared to what would be seen by an observer using both eyes, for the reason that the eyes are in themselves stereoscopic and can visualize height of objects. Obliques, however, do show hill features and objects in a way more or less familiar to the eye; whereas the verticals show the ground essentially in plan only. 49. Equipment: Cameras for aerial photography have in recent years developed from simple hand-operated types to large, power-driven, complex machines installed in the fuselage, some having as many as nine separate lenses. As the value of a photograph depends very much on the speed with which it can be produced, some planes are equipped with developing-tanks, so that the results can be studied without returning to their base. 50. The technical quality of photographs depends chiefly on the care with which the camera and other equipment are adjusted and used. To obtain the full value of photographs, the following facts must be known for each individual exposure: (1) Position, or area illustrated. Certain makes of large cameras are so constructed that much of this information is automatically recorded on the margin of the film at the time the exposure is made. This reduces the possibility of a photograph being misinterpreted--as for example, by reading it upside down, which "reverses the relief" and makes

|

|

- 22 -

78. The foregoing is intended merely as a brief indication of the general types of paint available; in practice there are, of course, many varieties in each class which are adaptable to different purposes. It is planned that specifications for such paints will be issued later. 79. Paints Suitable for Various Surfaces: The materials to which camouflage will usually be applied include corrugated iron, steel, asbestos cement, slates, stucco, concrete, brick, asphalt, and glass. Any of the paints mentioned above can be used, though in some cases only with special precautions; it therefore becomes a question of weighing durability against cost. Special paint requirements of various materials are as follows: Corrugated Iron, Steel. Oil paints and bituminous paints are the most durable: the other three classes tend to flake off non-absorbent surfaces. Asbestos Cement. Some modern factories are roofed with asbestos cement. If the sheets are new their alkalinity is destructive to oil-bound paints, and it is not possible to specify any particular age at which the alkalinity will cease to be destructive. It is therefore wise to apply an alkali-resisting priming coat before using an oil-bound paint. Oil-bound water paints are also affected by alkalinity, but not to such a serious

|

|

- 23 - extent. Bituminous or special alkali-resisting paint can be used without special precautions. Slates, Stucco, Concrete or Brick Walls. All five classes of paint are suitable, but an alkali-resisting primer may be required when using an oil paint on concrete. Asphalt. Only a bituminous paint should be used on a bituminous surface; any other type is liable to be spoilt by the "bleeding" of the underlying bituminous coat. Concrete Areas and Roads will be covered later by special instructions. Glass. If the blackout provisions do not take care of the matter adequately, it will be necessary to treat the glass of skylights in order to prevent "shine" (reflection), which can be seen for great distances. This is equally true of north lights, because often they are not oriented accurately, and in any case they are struck by the rays of the sun at sunrise and sunset in summer. (The 2nd Supplement revised the highlighted sentences to read: "If the blackout provisions do not take care of the matter adequately, it will be necessary to treat all glass areas that are exposed to the direct rays of sun or moon, in order to prevent 'shine' (reflection), which can be seen for great distances. These areas will include north lights, which, even if oriented accurately, will be struck by the rays of the sun at sunrise and sunset in summer.") If there is any objection to stippling them with the same paint that is being used on the roof, they can be covered with a clear varnish and then sprayed lightly with granite or similar dust of size that will pass a 2.0-mesh screen. Natural sand is not recommended for this purpose, as the individual particles shine. It will be found that with a little practical experience, adequate protection from shine can be obtained without cutting off more than half the light. If it is desired to continue the roof pattern over the windows, appropriately colored particles should be used. 80. Special Matt Surfaces For Roofs: The following are suitable materials for producing a matt surface:

|

|

- 24 -

81. General: Nets are used to break up outlines that are difficult to disguise by the ordinary use of paints. When stretched across portions of large roof areas and from the coping walls of structures, they introduce depths of shadow that are most effective in disrupting outlines. 32. Nets are of two kinds, fibre-rope and wire. The former are extensively used by mobile units of the Army on account of their portability. They may also be used in camouflage of large structures; however, they are not recommended for that purpose as they are quite perishable, and when garnished are difficult to maintain on account of their weight. 83. Rope Nets: Rope nets are made of rope previously treated to preserve against weathering. They are produced in a variety of standard sizes which can be combined as desired. When used on large structures they are supported by wire cables, which should be sufficiently strong to withstand high wind pressures to prevent their being blown away (Fig. 7). The nets are garnished in a variety of ways, e.g. by using cut vegetation (grass or branches of trees), strips of pre-colored burlap, and so forth (see "Garnishing Materials" below). 84. The mesh of most pre-fabricated nets varies from 2½" to 4", but among recent developments is a rope net of 8" square mesh, with burlap squares sewn into it in a variety of patterns. A variation of this design uses light metal squares, in place of the burlap, and these are painted according to the effect desired. These large-mesh nets are lighter in weight than the ordinary garnished net, which can be considerable when wet; moreover, they present only a fraction of the surface to the wind compared to the normally garnished net. 85. Emergency nets can be prepared in rapid time without weaving, by laying out a pattern to the size desired and fastening the intersections of the cross ropes with galvanized wire. 86. Wire Nets: Wire nets are much more desirable than rope nets for camouflaging large permanent structures, by reason of being (1) less subject to deterioration, (2) much lighter, (3) easier to maintain in place, (4) less of a fire hazard, and (5)

|

|

- 25 - cheaper. They are used for the same purpose as rope nets and are much more adaptable for the application of garnishing materials, which may be stapled or glued to the surface, interwoven, or simply tied. The nets are of the normal chicken-wire pattern, and the mesh used varies from 3/4" to 2", depending on the needs. 87. Garnishing Materials: The garnishing materials used for nets will be covered by special instructions. The conventional garnishing material is burlap, pre-colored burlap strips of which may be (a) woven into the mesh in any desirable pattern and spaced to give the depth of surface required for "tapering off", or (b) tied as streamers. (Fig. 8). 88. Important Points in Net Design and_Maintenaince: Diagrams showing the various methods of garnishing and hanging nets are included here as Figs. 8 to 18. Before installing any nets these drawings should, be studied carefully, and attention should also be given to the following points:

D. "SOLID-SURFACED" MATERIALS (FOR STRUCTURAL EXCRESCENCES). 89. The use of solid-surfaced, structural materials for camouflage has some advantages where certain surface textures are necessary, but on account of wind the supporting members must be properly designed if the "excrescence" is to remain as a permanent fixture. 90. Masonite, beaver board, plywood, or other building materials of this type may be used by laying out the pattern desired and attaching a rough framework on the underside (Fig. 19). These patterns are erected over areas, or attached to structures, to |

|

- 26 - break up definite outlines; but the scheme is costly, and the same effect can be obtained by using garnished wire nets. 91. Solid-surfaced materials have been suggested, for use in representing outlines of aeroplanes on dummy landing fields. These outlines are supported on a framework so as to cast shadows, and the upper surfaces are shaded, to represent the contour of the wing surfaces. 92. Smoke camouflage has definite advantages, and is currently being used, in certain countries in Europe for the protection of industrial areas, railroad yards, etc. The smoke is generated in pots similar to those used in the California orange groves and elsewhere, but designed to produce smoke rather than heat. The pots are set on the windward side of the area that is to be protected, and the smoke, although not dense when it reaches the upper levels, is sufficient to completely obliterate any view of the area. It has proved to be an excellent defense and is well recommended. The smoke is generated only when enemy planes are known to be approaching the vicinity. The methods of producing smoke haze are to be covered, in the handbook on chemical warfare. 93. Water areas, whether they be ocean, river, or canals, present features that are most conspicuous, and are generally accepted as permanent landmarks which cannot be concealed. Water has never yet been camouflaged satisfactorily except at a tremendous cost. Information in regard thereto will be covered by special instructions. 94. In regions of considerable snow fall, where the ground is liable to remain covered for considerable periods, it is suggested that important structures be painted, to match. This shade of white may have a light blue tinge, depending on sky reflections, over an extended, period, of clear skies, and should be judged accordingly- This shade will be particularly helpful in obscuring structures during the early morning period or towards sunset, when the blue tinge becomes more accentuated in the background. 95. The position of the sun should be observed if nets are to be erected, over areas liable to be in shadow. These nets should, extend over the limits of the normal shadow areas and slope off toward the ground.

|

|

- 27 - 96. The structures no doubt will have small shadows which are difficult to eliminate with nets. One should therefore endeavor to carry out a general shadow scheme on the nets; otherwise, the limits of the net areas are liable to be readily observed by virtue of their uniformity, and may nullify the effort of camouflage. 97. It should be remembered that the location is probably well known, and that under snow conditions it will be most difficult to obscure. Nevertheless, whatever is done to minimize any outstanding features may be the means of saving a hit. 93. When the snow season passes, the camouflage should be changed to meet the new conditions.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 6. Typical sub-station camouflage schemes.

|

Note: Rotated copy of the below image is available here.

|

|

|

Figure 8. Extending irregularities with garlands.

|

|

Figure 9. Garnishing.

|

Note: Rotated copy of the below image is available here.

|

|

Note: Rotated copy of the below image is available here.

|

|

Note: Rotated copy of the below image is available here.

|

|

Note: Rotated copy of the below image is available here.

|

|

Note: Rotated copy of the below image is available here.

|

|

Note: Rotated copy of the below image is available here.

|

|

|

Figure 16. Arrangement for erection of screen over long span between high buildings.

|

Note: Rotated copy of the below image is available here.

|

|

|

Figure 18. Methods of erecting

|

Note: Rotated copy of the below image is available here.

|

|

|

- 49 - BUREAU OF YARDS AND DOCKS STANDARD COLORS FOR CAMOUFLAGE The following four sheets show sixteen colors (or tones) tentatively selected as "standard" for camouflage purposes. Not shown on these sheets are matt black and matt white, which are also to be considered as "standard." It should be understood that the designation of certain colors or tones as standard does not imply that only those colors and tones are to be used in the execution of a camouflage scheme; however, they are intended to be used wherever possible. In extreme cases they may be blended as necessary, to produce any desired color or tone within the entire range of camouflage requirements. In blending, all paints used should be of equal quality. "Stapled over the original colors on the following pages are the revised colors, issued in September 1942 to made for better standardization. Copies of these same colors have been supplied to the leading paint manufacturers. The numbers of all colors in the revised sheets are followed by the letter (A). It is not intended that the issuance of these new colors should affect any orders for paint that may have been placed prior to their receipt, but it is desired that they be used in place of the old standards in future ordering."

|

|

The folowing color chips were photographed under an OSRAM Dulux L 35W/954 bulb at 1/125, ASA100 F5.6 with a Canon Rebel xTi camera. The color checker card is from X-Rite, formerly Munsell, and is a model 50111 (Amazon Link). If you give a damn about the actual color you will purchase one and calibrate the photos to same. Additionally, the greens and the browns are available on the Snyder and Short US Navy paint chips set #2 available here.

-Click to Enlarge- |

||||

|

SOURCE:

National Archives & Records Administration, Seattle Branch

Record Group 181, Puget Sound Naval Shipyard Captain of the Yard Passive Defense Files

Transcribed by RESEARCHER @ LARGE. Formatting & Comments Copyright R@L.

Miscellaneous Home | Passive Defense Home | Researcher@Large Home